Key Developments

Ideas and computers that introduced innovative solutions to problems in the early days. This walkthrough of the key developments and innovations in computer science is in chronological order, where possible. All dates are when the computer was operational. Note: The computer may have been in development for several years prior to this date.

CRT - Cathode Ray Tubes

You may be thinking that these were developed for computer monitors, but you'd be wrong. Long before that, they were used as a main memory storage, i.e. RAM. Huh?, I hear you ask. A voltage can be supplied to the CRT screen using the electron ray gun during a single pass on the screen. On the next pass the value of the voltage can be read by the gun. Thus the CRT "remembers" the voltage.

CRT core memory had the advantage that it was cheap, already proven as a technology (TV sets and RADAR) and versatile. Some computers used cathode ray tubes as accumulators and program counters. John von Neumann's IAS used CRT as core memory.

Mercury (Mg) Delay Lines

Before the CRT was widely used as a storage device, mercury delay lines were the standard, if anything from the dawn of computing can be called standard. It worked by having a long, thin "pool" of mercury and sending ultrasonic pulses down it as acoustic signals. The computer had the disadvantage that it had to wait for the signal to reach the far end of the line before it could read it. In real terms this was only a wait of less than half a second, but for a computer, even an archaic one, this is a very long wait. These were sequential memory, like the tape reels used in the mainframe computers of the 1960s - 80s.

The other disadvantage was that the lines were very sensitive to heat and had to be kept at a steady temperature, or you had to use several lines for synchronisation.

The sonic pulse is generated by a piezoelectric sounder in the delay line and travels along the line until it reaches the end where it is converted into an electrical pulse and sent to a repeater, where it was send back to the sounder, or send to the processor if a control line was set.

|

Mercury delay lines were developed for RADAR technology for synchronisation purposes. |

Magnetic Drum

This was the predecessor to the hard disk. A drum span at up to 7200rpm and a number of heads read the magnetic information on the drum as it span past. It usually stored information in decimal, rather than binary.

Drums are similar to mercury delay lines in their development. You had to wait for the part of the drum to spin past before you could access the data on it. The only difference was that the drum span so fast, that access was almost random. In this sense it was similar to modern hard drives.

von Neumann Architecture

The basic computer architecture proposed by John von Neumann was that computers should have their processors separate from their memory. This allowed the processor to use the "free" time while waiting for memory to return values, to perform other actions.

In addition to this, he also proposed that the processor contain these three registers; accumulator, program counter and index register.

Z1 (1936), Z3 (1941?)

Konrad Zuse built the Z1 in 1936 to aid him with his lengthy engineering calculations. It used sliding rods to represent binary values, forwards for 1, backwards for 0. The primary problem which slowed the development if this computer (finished circa 1938) was that the calculator (processor) exerted too much force on the memory rods and kept breaking or bending them. In fact, the processor never worked in concert with the memory. Synchronisation was the main stumbling block, and this was the reason that the machine took 2 years to build. It could only handle multiply, add, subtract, divide and square root operations. Its program was written on punched paper tape.

He built a further 3 computers. The Z3 was the same architecture as the Z1, but used relays instead of moving metal bars. Both were destroyed during the war, but were rebuilt later. The Z3 was a floating point machine. It was built during the war when there was a paper shortage, so film reel was used instead.

The Z3 used a floating point representation which is very similar to today's method. The first bit was the sign, the next 7 were the exponent and the last 14 were the mantissa, however, as the mantissa is stored in a normalised form, the first number of the mantissa is always 1, it can be dropped and the mantissa can have an extra bit.

Harvard Mark I (1944)

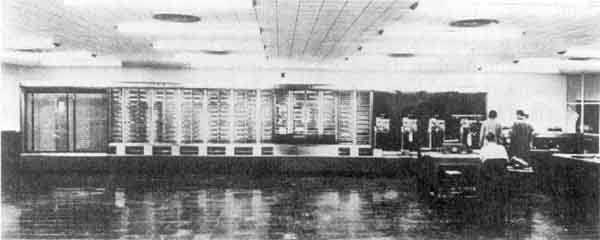

The MARK series of computers, developed at Harvard University by Howard Aiken with the assistance of Grace Hopper, began with the Mark I in 1944. The Mark 1 was a giant roomful of noisy, clicking, metal parts, 55 feet long and 8 feet high. The 5 ton device contained almost 760,000 separate pieces. It was used, by the US Navy, for gunnery and ballistic calculations, and kept in operation until 1959.

The computer was controlled by pre-punched paper tape and could carry out addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and reference to previous results ( it had special subroutines for logarithms and trigonometric functions and used 23 decimal place numbers ). Numbers were stored and counted mechanically using 3000 decimal storage wheels, 1400 rotary dial switches, and 500 miles of wire. Then the data was transmitted/read electrically and operated upon in a separate part of the computer, making the Mark I an electromechanical computer, not like the electrical computers of today. Because of it's electromagnetic relays, the machine was classified as a relay computer. All output was displayed on an electric typewriter. By today's standards, the Mark I, was slow requiring 3-5 seconds for a multiplication operation.

EDSAC (1949)

The Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Computer was the first binary serial stored program computer in the world, although this is arguable. It was a British computer. Hurrah!

In the EDSAC, 16 tanks of mercury gave a total of 256 35-bit words (or 512 17-bit words). The clock speed of the EDSAC was 500 kHz; most instructions took about 1500 ms to execute. Its I/O was by paper tape, and a set of constant registers was provided for booting. The software eventually supported the concept of relocatable procedures with addresses bound at load time. It used 3,000 vacuum tubes.

Visit the EDSAC simulator webpage to download this machine emulator for the PC.

UNIVAC (1951 onwards)

Built by Presper Eckert and Mauchly, the Universal Automatic Computer used a storage area as a "buffer" between slow input and output devices, such as a card reader and electric typewriter, and the main processor.

UNIVAC was the first US commercial computer. (The US census department is the first customer.) It had 1000 12-digit words of ultrasonic delay line memory and could do 8333 additions or 555 multiplications per second. It contained 5000 tubes and covered 200 square feet of floor. For secondary memory it used magnetic tapes of nickel-coated bronze. These were 1/2 inch wide, and stored 128 characters per inch.

Compiler (1951)

Grace Murray Hopper (1906-1992), of Remington Rand, invents the modern concept of the compiler, but it wasn't until 1952 that the first compiler, called "A-0" was implemented by her.

IAS (1952)

Started in 1946, this was John von Neumann's computer. IAS stands for Institute of Advanced Study, which is part of Princeton University. It used cathode ray tubes as its main memory.

Designers of the IAS were required to make their plans available to several other government-funded projects, and several other machines were built along similar lines. These included JOHNNIAC, MANIAC, ORDVAC, and ILLIAC. The IAS also influenced the design of the IBM 701, the first electronic computer marketed by Internal Business Machines (IBM).

EDVAC

During the construction of ENIAC, it became clear that it was possible to build a

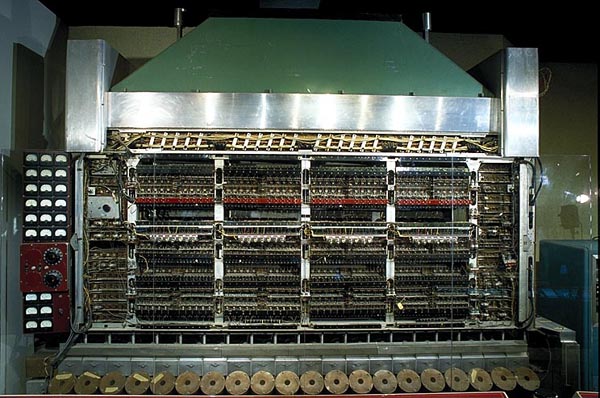

EDVAC (Electronic Discrete Variable Automatic Computer) was to be a vast improvement upon ENIAC. Mauchly and Eckert started working on it two years before ENIAC even went into operation. Their idea was to have the program for the computer stored inside the computer. This would be possible because EDVAC was going to have more internal memory than any other computing device to date. Memory was to be provided through the use of mercury delay lines. The idea being that given a tube of mercury, an electronic pulse could be bounced back and forth to be retrieved at will--another two state device for storing 0s and 1s. This on/off switchability for the memory was required because EDVAC was to use binary rather than decimal numbers, thus simplifying the construction of the arithmetic units. [10]

Taken from the History of Computing webpage.

Visit the Electronic Computers Within The Ordnance Corps website for the more details of the EDVAC.

UNIVAC 1103A (1954)

This computer introduced the concept of an "interrupt" The processor works on a problem, stopping to handle the transfer of data to or from the outside world only when necessary. All modern computers use interrupts to suspend processes when an input or output operation is needed.

IBM 650 (1954)

Drum memory had signed 10 digit decimal words and 2000 words of memory. Up to 10,000 words were available with additional drums.

200 read/write heads with 50 words per set of 5 heads read from and wrote to the drum.

IBM 1620 (1959)

The marked improvement of this model was there was no fixed word length! Each word was individually addressable. Each word was six bits wide -> 4 numeric, 1 "field mark" and 1 parity bit.

The 1620 did arithmetic digit-by-digit using table lookup. Add and multiply tables had to be stored at fixed positions in low memory. Divide was by subroutine, though optional divide instructions could be purchased to speed things up.

This was a sign of things to come. The 1980s are synonymous with companies selling wholly inadequate computers to firms and then charging to upgrade computers that were incompatible with all others. Not enough expansion ability was a key point built in so that a firm had to upgrade an entire computer system. See "More power to you" Essay on early computers. Arnold G. Reinhold

IBM 709 (1959)

This used a separate processor called a "channel" to handle input and output. This was in effect a very small computer on its own dedicated to the specific problem of managing a variety of I/O equipment at different data rates.

It is not hard to project this idea to the 80486 processor which is a 80386 processor and another 386 as a math co-processor.

As designers brought out improved models of a computer, sometimes they would add to the capabilities of this channel until it was as complex and powerful as the main processor - and now you've got a two processor system. At this point the elegant simplicity of the von Neumann architecture was in danger of being lost, leading to a baroque and cumbersome system.

The complexity of I/O channels drove up the cost of a system. Later the use of channels became a defining characteristic of the mainframe computer, although this term was yet to be coined. These computers were the standards of the 1960s. Eventually they would lead to faster processing, but simpler I/O machines, i.e. supercomputers, and to low cost machines, i.e. micro and mini computers.

IBM 7090/7094 (1962/1963)

This was the classic mainframe from the combination of performance and success (100s of machines sold).

IBM had made a loss on the 709. The 7090 was the same architecture but used transistors, not vacuum tubes, at the insistence of the U. S. Air Force, whom the first was built for.

7094 = 7090 + 4 additional index registers.

Large metal frames were used to stack the circuits (this is probably where the name mainframe comes from). These could swing out for maintenance. The density on the circuit boards was approximately 10 components per cubic inch.

The 7094 had a maximum of 32,768 words of core memory. This is about 150 Kilobytes Strangely enough this is the same as the first IBM PC (brought out in the 1980s). The 7094 had about the same processing power too. The 7094 could handle between 50,000 and 100,000 floating point operations per second.

The console was festooned with an impressive array of blinking lights, dials, gauges and switches.

"It looked like what people thought a computer should look like." [9]

"The operator's job consisted of mounting and unmounting tapes, pressing a button to start a job every now and then, occasionally inserting decks of cards into a reader, and reading status information from a printer. It was not that interesting or high status a job, though to the uninitiated it looked impressive." [9]

This is where the mount and umount commands in UNIX come from.

The number of cycles wasted by the average screen saver would have been scandalous in 1963. The batch processing of programs was to minimise idling the computer. It might be tempting for the programmer to gain direct access and run a program, getting results in a few seconds rather than in a few days. However the idle time of a few minutes setting this up was unforgivable given that the rental price was $30,000 per month, or between $1.6 and $3 million to purchase.

The 7094 used a 1401 computer for the slower input and output. The sequence went as follows.

Punched card --> 1401 --> tape reel --> 7094 --> tape reel --> 1401 --> chain printer

There was no direct connection to the printer, unlike modern computers.

Some had video consoles (for control purposes, sequential tapes gave no direct access to data) however the video console had a big appetite for core memory, so these were rare.

CDC 6600 (1965)

Most RISC concepts can be traced back to the Control Data Corporation CDC 6600 'Supercomputer' designed by Seymore Cray (1964?), which emphasised a small (64 op codes) load/store and register-register instruction as a means to greater performance. RISC allows faster operation of the processor, but sacrifices more complex op codes. These can still be performed, but take several op codes to achieve the same result.

The CDC 6600 was a 60-bit machine ('bytes' were 6 bits each), with an 18-bit address range. It had eight 8 bit A (address) and eight 60 bit X (data) registers, with useful side effects - loading an address into A2, A3, A4 or A5 caused a load from memory at that address into registers X2, X3, X4 or X5. Similarly, A6 and A7 registers had the same effect on X6 and X7 registers - loading an address into A0 or A1 had no side effects.

As an example, to add two arrays into a third, the starting addresses of the source could be loaded into A2 and A3 causing data to load into X2 and X3, the values could be added to X6, and the destination address loaded into A6, causing the result to be stored in memory. Incrementing A2, A3, and A6 (after adding) would step through the array. Side effects such as this are decidedly anti-RISC, but very nifty.

This vector-oriented philosophy is more directly expressed in later Cray computers. Multiple independent functional units in the CDC 6600 could operate concurrently, but they weren't pipelined until the CDC 7600 (1969), and only one instruction could be issued at a time (a scoreboard register prevented instructions from issuing to busy functional units).

Compared to the variable instruction lengths of other machines, instructions were only 15 or 30 bits, packed within 30 bit "parcels" (a 30 bit instruction could not occupy the upper 15 bits of one parcel and the lower 15 bits of the next, so the compiler would insert NOPs to align instructions. NOP = No OPeration, and act as buffers.) to simplify decoding (a RISC-like feature). Later versions added a CMU (Compare and Move Unit) for character, string and block operations.

Cray 1 (1975)

I include the Cray 1 because it was the fundamental supercomputer. This machine set the standards for all modern supercomputers. When it was powered up in May 1975, it was the most powerful computer on earth. The following article is taken from the Cray Museum Self Guided Tour, at the Smithsonian Institute. I have modified it slightly to increase the readability.

One of the remarkable things about the Cray series of computers was that, as a result of always improving systems and components, no two Crays are identical. Each one is an individual. The other thing that sticks in the mind about these computers is that they used liquid freon to cool the machine's components.

Seymour Cray, as computer architect, provided the technical vision of a CRAY-1 computer that was twice as fast as the CDC 7600 (12.5 ns for the CRAY-1 system vs 25 Ns for the 7600 system) and demonstrated balanced scalar and vector performance. The computer was also innovative in its use of reciprocal approximation for division. Harry Runkel was the chief logic designer; the machine was built primarily from nine off-the-shelf LSI circuits, which considerably shortened the development cycle. Seymour Cray, Harry Runkel, and Les Davis wrote about 1,300 pages of Boolean algebra to describe the approximately 100 different modules in the system. However, one of the biggest challenges was cooling the system; here, Dean Roush provided the mechanical engineering know- how to develop the cabinetry and cooling technology, for which he holds the patent.

Other technical staff who helped design and develop the CRAY-1 system included Gerry Brost, Roger Brown, Larry Gullicksen, George Leedom, Jim Mandelert, Rick Pribnow, Al Schiffleger, Dave Schulist, Ken Seufzer, and Jack Williams.

Serial No. 1 of the CRAY-1 computer system, the company's first product, was powered on in May of 1975 and officially introduced in 1976. Serial No. 1 (SN 1) was shipped to The Los Alamos National Laboratory in 1976 for a 6-month trial period. At about the same time, the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) persuaded Cray Research to add error correction to the CRAY-1 system and to begin the development of standard software. NCAR was Cray Research's first official customer. The company became profitable upon the acceptance of SN 3 by NCAR in December of 1977 (see photo). Because of the addition of error correction, SN 1 of the CRAY-1 system that is on display is 4 inches shorter and has 8 fewer modules per chassis than all other CRAY-1 computers and all CRAY X-MP computers. SN 1 was retired from service in the UK in May of 1989. See framed history.

CRAY-1 computers outperformed all other machines in their time and even today are recognised as having set the standard for the supercomputing industry. Applications of the CRAY-1 computer system include climate analysis, weather forecasting, military uses, seismology and reservoir modelling for the petroleum industry, automotive engineering, aeronautical engineering, space engineering, computerised graphics for the film industry, and so on.

Features of the CRAY-1 system include a fast clock (12.5 Ns), 64 vector registers, and 1 million 64-bit words of high speed memory. Its revolutionary throughput figures -- 80 million floating-point operations per second (Mflops) -- were attributed to the balanced vector and scalar architectures and to high-performance software that was tailored to efficiently use the machine's architecture.

The 5-ton mainframe occupies only about 30 square feet. This extremely dense packaging challenged the engineers responsible for removing heat generated by the modules. Thus, one of the most significant engineering accomplishments was the cooling system. Liquid coolant (Freon) is pumped through pipes in aluminium bars in the chassis. The copper plate sandwiched between the two 6 x 8 inch circuit boards in each module transfers heat from the module to the aluminium bars. The power supplies and coolant distribution system were craftily placed in seats at the base of the chassis. These seats were useful for checkout engineers who would sit on them when attaching oscilloscopes to test points on the modules. Examples of the modules and cold bars are in the display case. The CRAY-1 system contains about 200,000 integrated circuits, and its wire mat contains approximately 67 miles of wire. The first CRAY-1 computers each took a year to assemble and check out because of the large amount of hand wiring and assembly required. A continuous stream of engineering improvements and the customisation of the machines to satisfy unique customer requirements meant that no two CRAY-1 computers were identical.

The model designations A, B, and C, refer to the sizes of memory: 1 million words, 500 thousand words, and 250 thousand words, respectively. Although l7 CRAY-1A/B computers were built, no CRAY-1C computers were ever built. None of the original CRAY-1 systems are in service today; many of them have been retired to museums, including SN 14 at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C.

The requirement for standard software was a huge challenge. The company was faced with the need to deliver software with virtually no time, tools, or staff with which to develop it. One option under consideration was to contract out the effort. However, the programmers already hired, including Margaret Loftus who had been hired in May of 1976, prevailed on management and with the support of George Hanson, began developing COS Version 1. Staff was expanded and software analysts began the effort, building on a nucleus of code for EXEC and STP developed by Bob Allen in Chippewa Falls. In 1978, the first standard software package consisting of the Cray Operating System (COs), the first automatically vectorising FORTRAN compiler (CFT), and the Cray Assembler Language (CAL) was officially introduced. Dick Nelson, who is the company's first programmer analyst, is responsible for the design and development of CFT, the world's first automatically vectorizing FORTRAN compiler. [10]